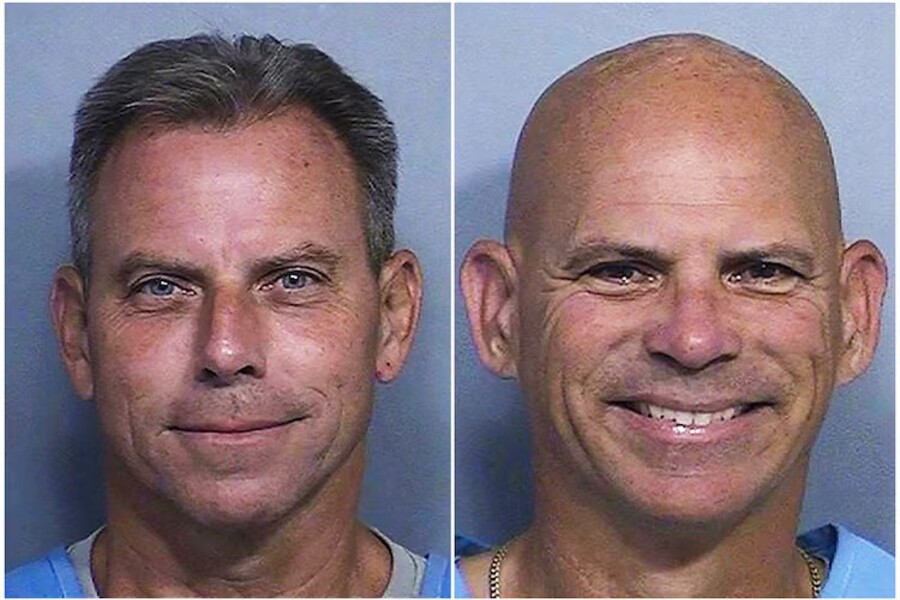

After 35 years in prison for killing their parents in 1989, Erik (54) and Lyle (57) Menendez will appear separately before California’s parole board this week—Erik on Thursday, Lyle on Friday—in proceedings that could open a path to their release or delay any chance of freedom for years. A panel from the Board of Parole Hearings will first decide whether each brother is suitable for parole based on rehabilitation, insight, institutional record, and public-safety risk. If either is granted parole, the decision next goes to Gov. Gavin Newsom, who can approve, deny, or modify the outcome. Finalization typically takes about five months; if approved through that process, release can follow immediately with standard conditions of supervision. If parole is denied, the board can set the interval to the next hearing at three, five, seven, 10, or 15 years. Newsom also retains independent clemency authority and could pardon or release the brothers at any time.

The hearings come after a major legal shift. Originally sentenced to life without the possibility of parole for the murders of Jose and Kitty Menendez, the brothers were resentenced in May by Judge Michael Jesic to 50 years to life, following an October recommendation from then–Los Angeles County District Attorney George Gascón. The revised sentence made them immediately eligible for parole consideration. At the resentencing, the judge cited unusually strong letters from correctional staff and acknowledged the brothers’ work to improve the lives of fellow inmates. Both men addressed the court and accepted responsibility. “I killed my mom and dad,” Lyle said, adding, “I give no excuses,” and admitting he had committed perjury in the 1990s. Erik told the court, “I committed an atrocious act… No justification for what I did,” while describing a long effort at personal change and promising, “I will not stop trying to make a difference.”

Lyle was 21 and Erik was 18 at the time of the killings. For decades, they have claimed they acted in self-defense after years of abuse by their father, an account that factors into how some supporters view their rehabilitation. The current Los Angeles County district attorney, Nathan Hochman, opposes release and has characterized the self-defense narrative as part of a series of “lies,” but more than 20 family members back the brothers’ bid for freedom and have submitted support.

Understanding the mechanics matters for readers tracking what happens next. A parole panel’s analysis centers on current risk, not re-trying the original case. That means the board weighs institutional behavior, programming, remorse, and realistic reentry plans against the gravity of the crime. Should the panel grant parole, Newsom’s review functions as a safeguard: he can let the grant stand, send it back with modifications, or block it outright. If the panel denies parole, the length to the next hearing reflects the board’s view of how much additional time or programming is needed before suitability could reasonably be reconsidered.

Parallel to the parole track, the brothers are pursuing a separate legal avenue: a habeas corpus petition seeking a new trial based on evidence they say was not previously available. The petition highlights two pillars: allegations aired in the 2023 docuseries “Menendez + Menudo: Boys Betrayed” by a former member of the boy band Menudo, who said Jose Menendez raped him; and a letter Erik wrote to a cousin eight months before the murders describing alleged abuse—corroborative material the defense says did not surface until years after trial, though the cousin did testify about the abuse. Earlier this month, Hochman filed a formal opposition asserting the petition does not meet the factual or legal threshold for a new trial, noting that juries rejected self-defense, multiple appellate courts affirmed the convictions, and calling the filing a “Hail Mary” that does not disturb those determinations. The habeas matter proceeds on a separate timetable and does not control the parole board’s suitability finding.

Why this matters now is twofold. First, the case is a high-profile test of California’s modern approach to parole in long-term homicide sentences, where decades of demonstrable rehabilitation and explicit acceptance of responsibility may compete with the enduring seriousness of the crime. Second, the outcome will set the immediate trajectory of one of the most scrutinized criminal cases of the last three decades: a grant could lead to release after administrative review; a denial could push the next opportunity years into the future; and any grant could still be altered by the governor.

For readers asking “what’s next,” the sequence is straightforward. The board holds Erik’s hearing on Thursday and Lyle’s on Friday, issues decisions on suitability, and—if there’s a grant—triggers the standard review period culminating in gubernatorial action. Separately, the courts will decide whether the habeas petition warrants any evidentiary hearing or relief. In the meantime, the brothers’ acceptance of guilt, their record in prison, the opposition from prosecutors, and the new evidence claims will all frame public understanding of whatever the board decides.

Bottom line: This week’s hearings are the Menendez brothers’ first credible chance at parole since their convictions. Whether that chance becomes freedom, a governor’s reversal, or a lengthy setback will turn on the board’s assessment of present-day risk and accountability, followed by Newsom’s review, while the separate new-trial effort unfolds on its own legal track.