Marion “Suge” Knight, the embattled former head of Death Row Records and a towering figure in the history of West Coast hip-hop, has stepped into the fray surrounding Sean “Diddy” Combs’ high-profile sex trafficking case. Speaking from prison, where he is serving a 28-year sentence for voluntary manslaughter, Knight emphasized that while Combs should face the consequences for any crimes he has committed, the music industry’s broader culture of abuse must also be addressed.

In a series of phone interviews with ABC News, Knight made it clear that scapegoating Combs alone would fail to address the systemic problems that have festered for decades in hip-hop. “If you’re going to make Puffy answer, make everyone answer,” Knight declared, using Combs’ longtime nickname. “Don’t get me wrong, he did terrible things, but he didn’t come up with those ideas on his own.”

Knight’s comments come amid Combs’ ongoing trial, where prosecutors allege he engaged in a pattern of coercion, intimidation, and sexual exploitation spanning years. Combs has pleaded not guilty and denies all allegations. The trial has captivated both the music industry and the public, with testimony painting a stark picture of alleged abuse, manipulation, and fear.

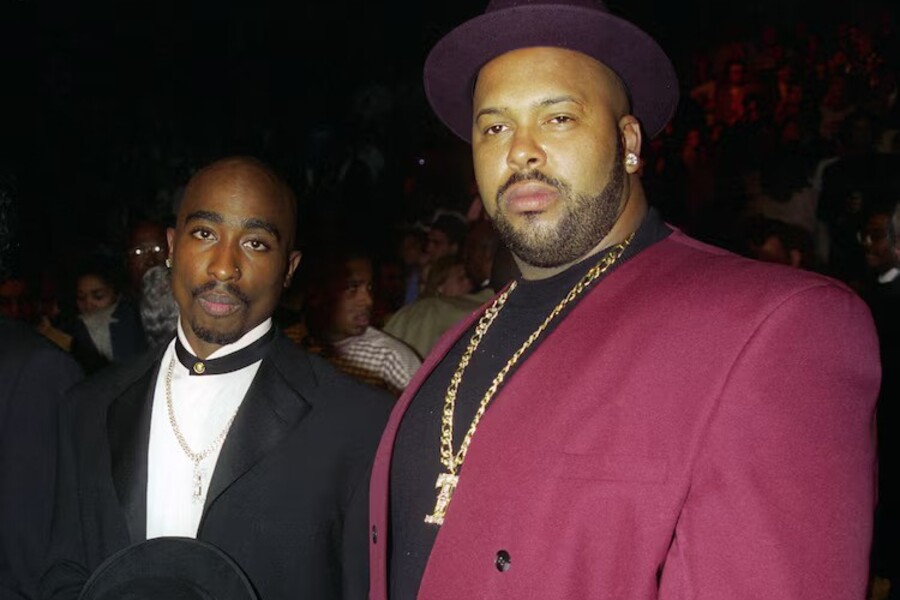

Knight’s legacy is no less complicated. As the founder of Death Row Records, Knight oversaw the rise of some of rap’s biggest names—including Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, and Tupac Shakur—during the genre’s explosive 1990s heyday. But his reign was also marked by allegations of violence, intimidation, and connections to the Bloods street gang. His eventual downfall came in 2018, when he pleaded no contest to voluntary manslaughter for a 2015 hit-and-run death. California’s three-strikes law lengthened his sentence, ensuring a long prison term.

Despite their history of rivalry—East Coast’s Bad Boy Records under Combs and West Coast’s Death Row under Knight—Knight insisted that their relationship was more nuanced than the media often portrayed. “I wouldn’t quite say we were rivals, because to say we were rivals means we had to be bad enemies,” he said. “He cared about the music industry. I think he loved the industry and did a great job with his artists.”

Indeed, both men helped shape the sound and business of modern hip-hop, though often from opposite coasts and with starkly different styles. Combs, known for his slick production and crossover hits, was celebrated for his ability to turn artists into pop sensations. Knight, on the other hand, forged an empire built on gritty street credibility and West Coast swagger, propelling gangsta rap into the mainstream.

But now, as Combs faces potentially life-altering charges, Knight suggested that the music mogul’s actions may be symptomatic of an industry that has long turned a blind eye to misconduct. Knight pointed to a culture that, in his words, rewards silence and punishes whistleblowers. “It’s a long list of people in the industry that’s unhappy because of the things they were being put through,” Knight said. “And that’s the sad part about it.”

One key witness in Combs’ trial, his former assistant Capricorn Clark, provided harrowing testimony about the power Combs allegedly wielded over her. She claimed that after she stopped working for him, his influence effectively blacklisted her from jobs elsewhere in the music business. Knight, who employed Clark at one point before she worked for Combs, described her as a hardworking woman who became trapped in a no-win situation.

“She did great things for Puffy,” Knight recalled. “Anything he wanted, she made it happen.” He added that Clark once confided in him that she had been warned not to speak out against Combs and that she was allegedly paid for her silence—a tactic Knight said was all too common. “If you go get a job at Universal and Puffy makes a phone call, you’re not getting that job,” he explained. “If you go get a job at a counter agency or in the movie business and Puff makes that call, your career is over.”

Knight’s insight reflects a stark reality: the music industry’s intricate web of power and influence can make it difficult for victims to come forward, let alone find justice. Knight emphasized that Combs was not the only one to benefit from such dynamics, nor was he the first to use them to his advantage. “Don’t get me wrong, he did terrible things,” Knight repeated. “But he just didn’t come up with those ideas on his own.”

While Knight acknowledged the seriousness of the charges against Combs, he also recommended that Combs consider a plea deal rather than endure a lengthy and public trial. “If there’s a situation where he can do some time, but not a lot of time, go knock it out,” Knight advised. “Don’t keep torturing yourself,” Knight spoke from experience: he, too, took a plea deal rather than risk a harsher sentence at trial.

Knight’s reflections extended to Combs’ personal life. He noted that Combs’ family, including his children, has remained by his side during the proceedings—a situation Knight described as both admirable and heartbreaking. “It’s not easy for the kids,” Knight said. “Once he gets where he’s going, to a real prison, he’ll be able to take a step closer to freedom.”

Knight also rejected the idea that Combs invented the coercive tactics prosecutors describe. “I think he repeats what he’s seen,” Knight said, referring to a cycle of abuse and exploitation in the music business that stretches back decades. “He repeats what he learned.”

The trial has also resurrected old stories about Combs and Knight’s supposed rivalry, including an alleged confrontation at Mel’s Drive-In diner in Hollywood. Combs’ former personal assistant, David James, testified that in 2008, Combs expressed a desire to confront Knight and his entourage at the popular late-night spot. Knight laughed off the suggestion that the encounter was anything other than routine. “If anything is suggesting that I was doing anything illegal, I’m gonna say, definitely not,” he said. “Anybody that knows me, from two o’clock in the morning to almost six o’clock in the morning—I’m always at Mel’s with six or seven pretty women enjoying myself.”

Knight even suggested that Combs had a secret admiration for Death Row’s music, citing stories that Combs would listen to Tupac Shakur and other Death Row artists on his yacht. “I was surprised about that,” Knight admitted. “I hope he wasn’t jealous of me, ‘cause if he was jealous of me, that means he was liking me too much.”

Knight concluded by expressing empathy for Combs’ current situation. “I know he feels that he doesn’t have a friend in the world,” Knight said. “None of them has been to court. None of them has been a help. So I’m quite sure he’s in a lonely place right now.”

As the trial continues, Knight’s comments offer a complex perspective on the allegations against Combs. They remind the public that the story of Combs—and indeed, the story of hip-hop itself—is not just one man’s fall from grace, but a reflection of an industry that has long blurred the lines between power and abuse, art and exploitation.